Millennia after its imperial apex, Rome continues to have immense visibility in the world. Here was developed, over 2,000 years ago, the very concept of a transportation system connecting the widest reaches of its empire with paved roads, maritime routes, navigation canals, ports, stocking and rest areas, and integrated systems for the rapid transportation of products, passengers and information.

But ever since the invention of mechanically propelled vehicles, Rome has been lagging in its ability to innovate. What was once the pinnacle of infrastructure and planning now has the worst mobility in Europe.

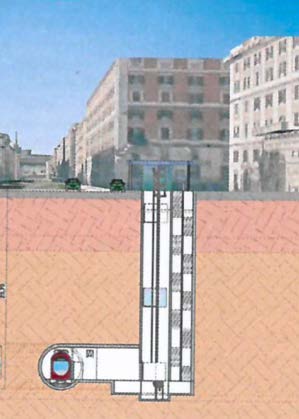

Its famous and vast archaeological remains buried up to a depth of 30-40 meters have so far constituted a critical obstacle to developing an effective underground transport system, at least using traditional technologies. As of now, Rome only has two completed subway lines, and a third one still under construction, all using traditional heavy trains and infrequent service.

The Strategic Plan for Urban Mobility proposes employing 100% electric and driverless people movers, small-diameter tunnels and small footprint elevators, and the digital optimization of the transportation system.

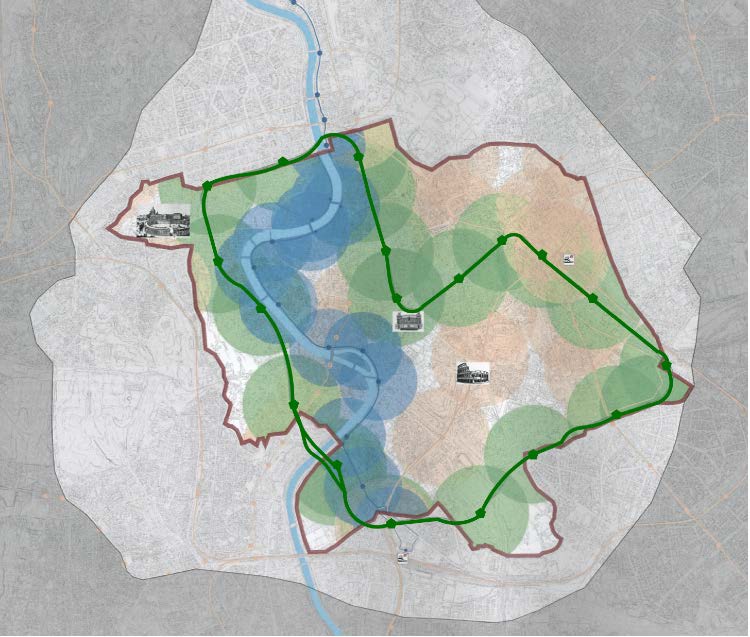

Its objective is to liberate the largest pedestrianized area in the world — an area of roughly 20 km2 — which would include Western Europe’s largest archeological area and a cornucopia of ancient, medieval, Renaissance, baroque and modern architectural and artistic treasures dispersed throughout the living city fabric.

The project envisions the rebirth of Rome’s historic center, not as a playground for tourists, but as a nodal hub for the global creative knowledge industry. It aims to revive Rome as a desirable place for the creative arts, global think tanks and conferences - and daily life for its people, as it has been repeatedly over the past two millennia. Tourism will benefit from improved mobility but remain secondary to the true life of the city.

Current construction of traditional invasive metro line in central Rome

How does moving configure living?

Red bounded area pedestrian only (corresponding to the grey area in the map on upper right)

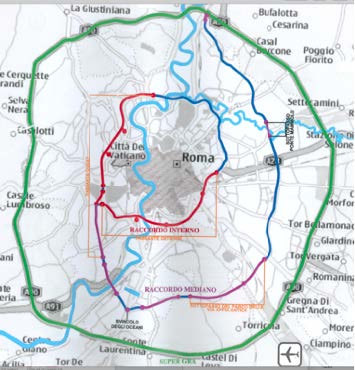

The Strategic Plan for Sustainable Mobility, drafted by Antonio Tamburrino at the request of Rome's Mayor in 2012, proposes a 5 Ring solution to Rome's transprotation challenges.

The plan calls for the elimination of private motor vehicles from the city center, thought not from greater Rome, where a new generation of cleaner, autonomous and shared electric vehicles will continue to serve the city's residents and visitors, thanks to improved surface and subsurface arteries (rings 1-3).

Clean mobility solutions from walking and cycling to emerging electric micromobility options benefit from (and make feasible) the vast pedestrian zone served by the Tiber Tramway and the Central Loop (rings 4-5).

Key to implementing the Five Rings plan and in particular the Central Loop is a technical solution to the problem of non-invasive tunneling below the city's rich archaeological strata.

The Central Loop is conceived to weave its way at the minimum possible depth below the ruins (as little as 12 meters below the surface) through tunnels with a diameter of under five meters.

With small cars (16-25 passengers) and frequent automated service (even every 60 seconds) stations can be virtually eliminated, replaced by elevators which provide direct access to vehicles, thus reducing archeologicals impact.

The company which provides this solution will chart a crucial role in the next phase of Rome's evolving history.

Section of Central Loop proposal

all roam into Rome

The force of Rome has always sprung from its transit capacities. It begins with the major river artery, first called Rumon, akin to its city and founder alike. From the early hill tribes and their tangles around the Tiber and its reach to source and sea, to consular roads and latter-day rails erupting from the Servian and Aurelian Walls, the mobility of Rome has long been index of the city's vitality, initially brewed from the confluence of Etruscans, Greeks and Latins.

Ironically, Rome's metabolic ways facilitated both outward conquest and inward crush. When beaten down to its nadir in the 7th-century, the city was kept afloat on its own ruins by these same conduits. Through the complex dance of Pope, King, and Emperor from the Middle Ages on, Rome once again resurged, a jewel of the Renaissance and Grand Tour, only then to be flattened by a burdening modern state.

From the 1870 unification of Italy to the era of dolce vita a century later, Rome became sieged by its own new mantle as Roma capitale, its river choked off from the people and squatted by ungainly government blocks. The postwar boom only swamped the traffic with motorized rubber and unchecked growth in the periphery, with no viable public connectivity but a skimpy metro, a lumbering tangle of bus lines, and disjected outward access.

This dire dysfunction and the recent flood of mass tourism have now pressed Rome to a new low, far behind other major global cities in vibrancy, motility, and livability. It is time for Rome to liberate itself as people and place from the scourge of long stagnation and get back on the map through fluid mobility for a greener century.

With a multimodal nexus of light rail, tunnels, loops, roads, and trams, Eng. Tamburrino proposes to transmobilize Rome with a fresh system of "five rings and a string." Starting with the Tiber Tramway and the river's sluicing, the plan claims to redress the city along its natural axis, redintegrate the pulse of center and periphery, respawn the largest-yet pedestrian urban core with rhythmic motion and life. This would free the familiar streets and quarters by halving - in keeping with EU goals - the current carbon emissions and auto traffic, replacing them with a pulsing interplay of people, biota, and cultural performance. The resulting urbs could again, reconditioned, become an earthwide goad for creative knowledge and webbed life, nurturing to residents and visitors alike. The way in which this may happen could be a communal venture for the whole Open City for decades to come.

In our study and engagement with Antonio himself, we found much to admire, and as much to ask and probe. Certainly the stated purpose and intended results for the City were encouraging and would even extend larger urban trends and ambitions elsewhere: Singapore, Curitiba, Vienna, Kigali, Paris, Barcelona... Not being in a position to assess the strictly technical aspects of the project, we did appreciate its stated goal of slashing the car traffic and carbon emissions and creating greener social space, not to speak of the liberation of the Tiber to its own larger belt. Still, we offer several periblematic questions:

(1) If the bane of mass tourism is also a function of growing middle classes across the globe, would a greater capacity of the City to move people simply be playing catch-up to the continually swelling tides of tourists? Would it not be just as important to induce folks everywhere to be more content where they are without extravagant trips or bucket lists to check off? For that matter, what might some provisions be to enable a 15-minute city for Rome's residents, so they would be able to do most of what they need and want to without having constantly to cross the city? In other words, would one form of energy saving engender an increase in new forms of energy consumption?

(2) Who would benefit most from the enhanced livability of Rome? If the historic center is already prohibitively expensive, wouldn't an improved city only augment the cost of living at the center? What would it take for all neighborhoods to be happier places to dwell, or would the periphery simply become the displaced parking lot for the City? What cultural and ethico-spiritual shifts would need to be afoot for Romans to dispense with cars altogether, and not just in the historic city? The buy-in cannot be assumed or superficial. People will need, for example, to give up driving to discount supermarkets and buying mounds of toilet paper at a time. Instead they will have to walk more often to closer shops, as in the pre-car past, and buy less at a time. How do you put that proverbial genie back in the bottle?

(3) It seems that, for a project like Antonio's to reach its own aims, it also has to galvanize a much larger sociopolitical movement and enlist wide participation in the buildout of a full cultural transformation. What do you tell all the bus and cab drivers of the present they should do instead for a living? What alternatives and incentives need to be offered? Would high tech swoop in and simply colonize the city anew? In sum, Carless Rome can only succeed if the whole city dives into a vast collective experiment before, during, and after all its infrastructural segments. A top-down approach will surely fail.

(4) Lastly, we had learned of the concept of operational land that always keeps visible the command-control relations between "city" and "country." To reduce the extractive power of a city, it would be necessary for it to become more self-sufficient - even frugal - in energy, food, material use. How does that happen? When Dilip da Cunha sat in on our engagement with Antonio, he posed the question, why do we even speak of the city at all? Isn't everything an open network? If so, it also seems that that network is also a highly graduated one in which nodes we call cities and towns require a major shift in their synaptic habits within and without.

Dear people, what do you think of all this?

David U.B. Liu, Mangroves, 2023

a spiritual metamorphosis alongside/through transmobility?